The Border is Complicated, and So Are Texans' Feelings About It

What we learned when we traveled to the southern border

I am not a border or immigration expert and I will never claim to be. Texas is a vast state and we lived 350 miles from the closest border crossing. But two trips to the Big Bend region taught us a lot that we didn’t already know about our southern border. This piece was adapted from the piece I wrote immediately following our family’s 2018 trip to Big Bend National Park.

Growing up, my family made frequent trips to Canada to visit my grandparents, who lived in three separate provinces at different times until I was in high school. When we lived in Detroit, a trip across the border was no big deal and Canada was just another place that was a little different because everything was in English and French. When I was in high school, I spent one summer on a youth ministry travel team throughout Texas. One of our stops was El Paso and while we were there we made a couple-hour trip to Juarez. Of course, this was pre-9/11 so we didn’t need our passports, but that memory of our simple trip across the border has stuck with me over the years. Juarez wasn’t as scary as I hear people talk about today and people weren’t out to get us. The biggest danger that we faced in Mexico was Montezuma’s Revenge, which hit half of our group who took the risk and drank the ice water during our lunch stop at a real Mexican restaurant.

In 2018, our family planned our first of two trips to Big Bend National Park. One of our goals was to prepare for the border crossing at Boquillas. All of us were excited about the prospect of spending a couple of hours shopping and exploring the border town right across the Rio Grande. We spent a Saturday afternoon after soccer games traveling to the public library in downtown Houston so we could submit four passport applications for the entire family. I think our seven-year-old son was the most excited out of all of us. He couldn’t wait to return from Christmas break and tell all of his friends that he had been to Mexico.

While I wanted to visit Mexico for the sake of visiting Mexico, I also hoped our kids’ first time out of the country to be as mundane as my many trips to Canada during my youth. I didn’t want them to see Mexico as one of two extremes: an expensive destination vacation or a mission trip to help the impoverished. I wanted them to see Mexican citizens as normal people just living their lives, only they were speaking a language our kids were just beginning to understand.1 When we talked about visiting Boquillas, I reminded our kids to respectfully use their limited Spanish-speaking skills because we would be visitors to a foreign country.

But then, the 2018 government shutdown closed down all of the facilities in the national park, including the border crossing. Instead of exploring Boquillas, we had to look across the pristine Rio Grande to get a glimpse of another country. Another country that on the surface looked just like the soil we were standing on.

I am Northern-raised, born to two Northerner parents who made sure I saw plenty of the country growing up but always considered the Midwest “home.” I say this because I know that this is one of many factors that affects my perspective on border issues. For six years, we were Texans by choice, but constantly reminded that were not true Texans, born and raised. (Refer to my piece about Texas pride to get a little more insight into that particular reality.)

Yet since early adolescence, I’ve been fascinated by the contradictory, sometimes troubling, and always colorful history that belongs to the Lone Star State. This is why, over the six years that we lived in Texas, I made sure that our kids got to take in as much Texas history as possible.

And part of what makes that history so complex and fascinating is the sweeping river that divides Texas from our southern neighbors, and the barren desert land that Mexicans and Texans spent much of their shared history working together to conquer and attempt to inhabit.

On our two trips to the Big Bend region of Texas, one of our stops was Terlingua Ghost Town, which dried up after the end of mercury mining in the local mountains. One of the many things that makes Terlingua's history so fascinating is the relationship that the American citizens of Terlingua, Texas had with their Mexican neighbors. During the late 19th century and early 20th century, Mexican miners freely commuted between the mines and their Mexican homes, a practice that benefitted both the Mexican workers and the American mine company. The longer I've lived in Texas and the more that I've read, I've come to understand that this is something that has been a natural part of border life, a historical fact that complicates much of our current immigration narrative.2

Yes, we have serious immigration problems in need of comprehensive reforms ranging from how we vet applicants to what should be done with those who were brought here when they were too young to make the decision themselves. Yes, we need secure borders to the north and to the south to make sure that people who want to harm United States citizens are not coming into the country. Yes, our system is overrun with too many applicants and too few judges, lawyers, and border patrol agents to process and track those seeking legal entry into the United States once they cross the border.

No, we should not just let anyone and everyone freely walk into the country with the expectation that they will be given a job and a free education.

But we need immigration. It is a good thing that people from all over the world still want to come to the United States. It is a good thing that people still believe that it is the best option for their family. It is a good thing to welcome diversity of experiences and knowledge and skills into a country that needs to stem the tide of population decline. Instead of seeing immigration as a net-negative that will destroy our American “culture,” we should see it as a challenge to be met with compassion and innovation that could make our country stronger than ever.

I know that many outsiders have watched the behavior of Texas government officials with horror as the governor has sent migrants on busses to northern cities in the dead of winter and set up brutal barriers while ordering national guardsmen and border patrol agents to not intervene while watching women and children attempting a border crossing die right in front of them. People believe the worst of Texans and other southern residents, convinced that they support the brutal tactics of elected officials and that everyone in border towns feels the same way about those choosing to cross desolate deserts, mountain passes, and rivers to come to the United States without legally entering through crowded and overwhelmed entry points.

There are others who have listened to the rhetoric of a legitimate crisis at our southern border and have convinced themselves that countless border cities are overrun with hordes of people making the difficult journey across desolate deserts, mountain passes, and rivers, who are then finding themselves lining the streets of these towns that are not equipped to handle the needs of hungry, desperate people. And yes, some towns have more bodies than resources to handle them. Others do not. Like all things, border towns are not a monolith. And you can talk to two people from the same border town and they will most likely give you a different assessment of the situation and solution for the problem.

Living in Texas taught us just how complicated the situation is, and understanding that the vast majority of the state does not live within 200 miles of the border is also an important piece of the puzzle. Immigration, for better and for worse, is just a part of Texas history, culture, and the economy.

In 2018, the first time we visited Big Bend, a recent poll had shown that 54% of Americans opposed building a wall in the fashion that Donald Trump was demanding, even though 81% believed that border security was an important issue. Emotions were high as we traveled in the region. One of the more telling signs that we saw close to the border was a sign right outside of Terlingua with these words: “Resist! No Wall. Rednecks for Beto.”

In the years that we lived in Texas, I learned that even in a border state, the feelings are very mixed, and those feelings don't have a political affiliation. That became abundantly clear when I spent the days before our 2018 Christmas break vacation reading the comment threads on the Big Bend National Park Facebook page. There were plenty of Texans who were upset with the idea of the wall and the impact this was going to have on their vacations and, even more importantly, on the state.

But now the thought of a wall is becoming increasingly popular with people of all political persuasions. According to recent polling, for the first time in a long time, a majority of Americans support the building of a wall. But one visit to the region driving along the southern border shows just how difficult and potentially destructive building a wall can be. It is a bandaid solution to a problem that is so much bigger, a point that was highlighted by this particular episode of Pantsuit Politics.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, what happens in other states matters to us. It affects us. And finding solutions to our decades long standstill with immigration reform is affecting all of us. In a recent blog post put out by CATO Institute, Alex Nowrasteh argued that

“…expanding legal immigration is the only way to reliably and permanently reduce illegal immigration so long as the United States is a desirable destination…Other than crashing the economy, expanding legal immigration is the only reliable way to massively reduce illegal immigration without committing crimes against humanity.”

We need solutions, not the GOP playing election games with desperate people’s lives and our national economy and security. And we need more people to spend less time listening to sound bites on TikTok and reading the fear mongering on Twitter3 and actually spending time learning about the border and seeing it for its rich, complex history. Americans have always looked at immigrants with suspicion and fear. In the 21st century, I would like us to find a better way.

We all finally got to go to Mexico the following year when we returned to Big Bend for our 2019 Christmas Break trip. We sailed across the river and rode burros into Boquillas. We enjoyed lunch at a restaurant, drank from cold Coke bottles, and walked down the main street. We purchased trinkets and then crossed the river back into the United States. That was just one afternoon in a memorable family vacation, but the mundane nature of crossing the border and mingling with our southern neighbors stuck with our kids, just as I wanted it to.

And it gave our whole family a little more perspective on a complex issue that needs a series of interconnected solutions. I just hope we figure it out sooner than later.

Support my writing

While most of my work here is free for all subscribers, it is still a labor of love that I fit into the few hours I have when I am not teaching or being an attentive wife and mom. If you would like to support my writing but do not want to commit to being a paid subscriber, please consider a one-time donation.

You can also support me by ordering my book or books from my favorite book lists at my Bookshop.org affiliate page.

If you want to be a regular supporter, you can upgrade your subscription from free to paid and get occasional content only for paid subscribers.

And thank you for supporting my journey 💗

While it was pretty limited, our kids did get Spanish lessons at the Lutheran school they attended just north of Houston.

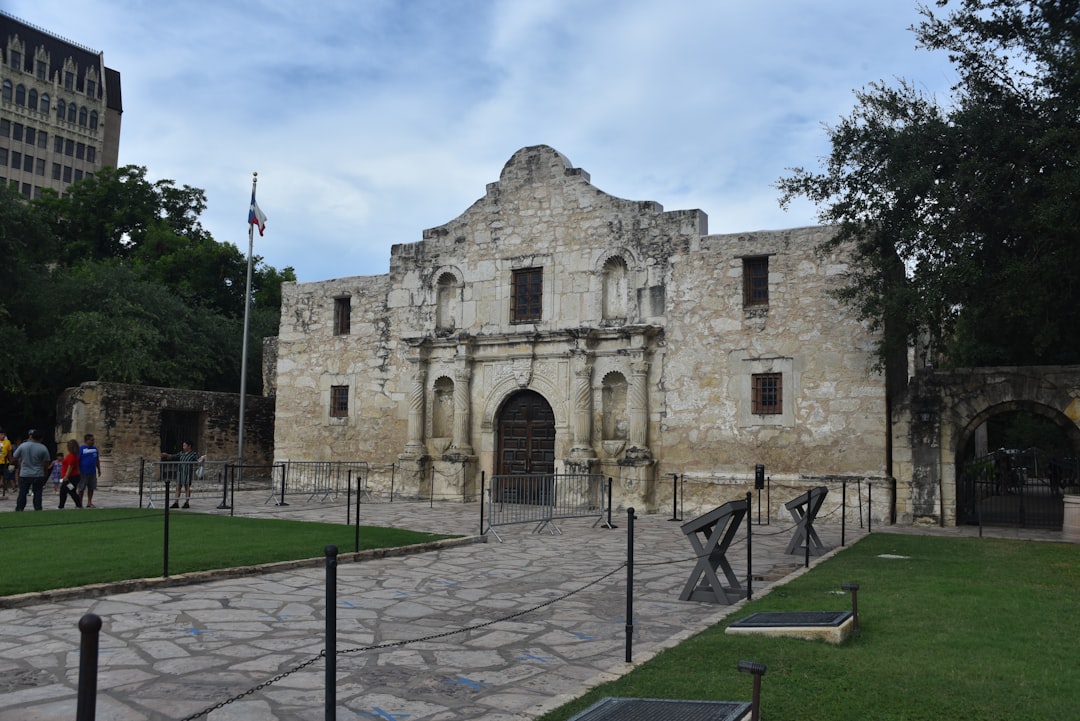

I was also struck by the irony in a state with people who complain about illegal immigration when the state was formed through the illegal immigration of American citizens moving into the territory against the will of the Mexican government, often pushing out the Tejanos who had settled the territory for generations. For more information, I highly recommend reading Forget the Alamo, by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford.

Sorry, I refuse to call it X.

Love your insight!

Twitter it will always be, I agree. It seems a shame that immigration is such an emotive issue. The very fact of this seems backwards. Why is it such an issue that we might be faced with people who are in some way shape or form different to us? I believe that the idea we are competing over scarce resources is inherently incorrect and down to ideas that have persisted formulated by thinkers such as Malthus. Yes institutions may reach capacity and infrastructure needs investment time and time again. Neither of these problems is even slightly beyond us in the present age.